There is something you should know about the word thingy (dinges in Dutch). It refers to something, but what it represents is at the same time unknown. So how come this yet seems to work, linguist Marten van der Meulen wonders.

My wife: Hey Mart, are you upstairs? Can you bring the thingy with you?

Me: Okay! (And I bring the object with me that my wife referred to).

Has this ever happened to you? I dare say it has. In fact, I think people use thingy all the time. For example, the brothers and sisters of thingy, or that one (die ene), whatshername (hoeheetze), whatchamacallit (je weet wel), so-and-so (huppelepup), and most likely all kinds of other words (my favourite is the English thingamabob).

These are all words that you use when you can’t remember someone’s or something’s name. Words that in a way hold the spot of the real word, while that real word has stepped out for a sec.

So thingy is a phenomenon that is used every day. Yet thingy is also quite an exceptional word. The type of words that thingy refers to is in fact incredibly strange and interesting. Think about it; normally we distinguish two types of words: content words and grammatical words. All content words have a referent. Those words refer to something abstract or concrete, such as jealousy

or dog. Names refer to specific people, whereas the same name can refer to different people (even when your name is Marten van der Meulen). But the name still refers to all these specific individuals.

Grammatical words are already more interesting, because they don’t have a referent, but indicate relationships between specifications of words. He didn’t come because he was sick. There is a big difference between the and a dog. And then there are interjections like yes hello and ouch, and you

and thus and this and grrrr.

'Thingy' is one of those words that in a way hold the spot of the real word, while that real word has stepped out for a sec

Then again, we soon get into all sorts of issues about the meaning of words and word classes. That’s not my point. My point is that despite the huge variety of words, thingy

manages the do something unique. It’s no lubricant that you need to structure the sentence (as grammatical words do). But it also doesn’t refer to anything. It does refer to something specific, but you don’t necessarily know what that is. And whatever it is, can differ per situation.

The second special thing about thingy is that we understand what it means in the first place. How do I know, in the marital dialogue above, what my wife wants? In order to understand this, we have to talk about meaning in context, which plays a big role in everyday language in many ways. The best known is probably through so-called deictic

words. These are words whose referent can change. Words like you, here

or yesterday do not refer to anything specific: what they refer to depends on the context. What is here for me, might be there for you. And what is tomorrow today, is yesterday the day after tomorrow.

Another example of meaning in context is pointing. Pointing is generally one gesture. Pink, ring and middle finger curled inward, thumb on top (or in the air), index finger extended. Basically, pointing always has to do with creating shared attention. The person pointing the finger focuses on something and wants someone or multiple someone’s (someone’s? hmmm) to do the same.

But there’s often more to it than that. The nice thing is: not only does pointing have multiple meanings, we almost always know immediately which one is used. Consider the following three scenarios:

a) You are sitting in a restaurant and your plate is empty. A waiter comes up to you. He looks at the empty place, turns around to another waiter in the background, snaps his fingers, and then points to the plates.

b) I’m at the same restaurant, and not my plate, but my glass is empty. I make eye contact with the waiter and point to my glass.

c) I run into a friend at the train station. We don’t greet each other, but point at each other.

I will further explain, but I think everyone understands. In the first scenario, the plates are cleared. In the second scenario, my glass is refilled. In the third scenario, there is mutual recognition between us: I see you; I recognize that you are here. Maybe with a touch of surprise: hey you’re here too! Everything runs smoothly, nothing goes wrong. My glass hasn’t been removed; my plate hasn’t been filled up. We know by context what pointing means.

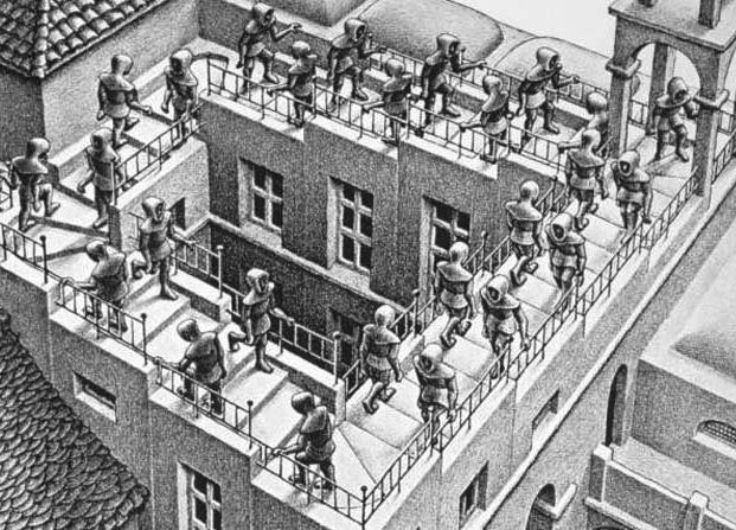

The nice thing about meaning in context is that it causes language to lose an enormous amount of its potential ambiguity. Because while something may be open to multiple interpretations without context, some of these interpretations are partially or fully cancelled out by the environment in which it takes place. This is illustrated by typography spacing mistakes.

It can become clear that context plays an important role in the interpretation of language. But that still doesn’t get us any closer to thingy. For that, we need one more element: common ground. It’s simply the amount of shared knowledge that you have with someone else. The more shared knowledge, the less one needs to specify.

The better you know one another, the less specific you need to be in your language

That’s why it works. I know, perhaps by experience, or by a previous comment, or by watching what she is doing, what my wife means. Surely if I were standing in the supermarket with just anybody, and that person asks me to grab a thingy, it would be a lot less likely that I understand what he/she means.

So, the better you know one another, the less specific you need to be. Maybe you can even do a little experiment as a relationship test. For people reading this who recently started dating someone new: try pointing at a new thingy every next week in your relationship. Find out how quickly you have common ground!